Claudia Andujar: The Yanomami Struggle

Exhibition Texts

Claudia Andujar's retrospective dedicated to the Yanonami, Native Brazilians at risk for extinction, presents hundreds of images and an installation by the photographer/activist, as well as books and documents that chronicle the trajectory of these people on their quest to survive. The exhibition, shown at IMS Paulista between January 2018 and April 2019, and at IMS Rio between July and November 2019, outlines a wide panorama of Andujar's extensive work along the Yanomami, recapturing little known aspects of the photographer's struggle for the demarcation of indigenous land, an activist aspect that led Andujar to bring her art together with politics.

The showcased material is the result of several years of research by curator Thyago Nogueira, coordinator of contemporary photography for IMS, within the institute's archives, with over 40,000 images by the artist.

After settling in Brazil, Claudia Andujar traveled the country from north to south. She used the camera as her compass and mealticket. Her closeness to anthropologist Darcy Ribeiro led her to the Karajá people (1957), then to the Bororo (1964) and the Xikrin (1966). Along with photographers like George Love, Maureen Bisilliat and David Drew Zingg, she was part of the original staff of the magazine Realidade, where she produced immersive features and deepened her interest in marginalized groups like prostitutes, homosexuals and migrants.

Andujar had already developed a body of work consistent with social documentation, inspired by American photographers such as Minor White and W. Eugene Smith. Encouraged by her husband George Love, to whom she was married from 1968 to 1974, she went on to expand her experimentation, introducing new filters, films and projections.

Her first contact with the Yanomami took place on assignment for a special issue of Realidade dedicated to the Amazon (1971), which examined the region in order to discuss the government’s plans for developing it under general Emílio Garrastazu Médici (1969-1974).

A grant from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation was the impetus she needed to quit the magazine and dedicate herself to a long-term project. The plan was to document the Xikrin Indians in southern Pará. She changed course when she learned of an even more isolated group, the Yanomami.

In December of 1971, Claudia Andujar and George Love came to the Catrimani River basin in Roraima for the first time. They spent four days there, unaware of the impact that this trip would have. Between 1971 and 1977, Andujar went back to the Yanomami region of the Catrimani on countless occasions to develop her project, received by Italian missionary Carlo Zacquini, who himself had been there since 1965. Zacquini opened her up to an unknown world.

During her first visits, Andujar accompanied the daily routine of the community, documenting them with certain journalistic neutrality. “The photometer stopped working because of the humidity. I had to shoot at a wide angle and on 3200 speed film all day. Normally the forest is dark enough as it is, but when it’s cloudy

and raining, it gets even darker,” she recounted in 1974.

Over time, feeling more at home among her new friends, she grew closer to the groups of families and immersed herself in the forest. She participated in long expeditions of collective hunting, when whole groups camp in the forest to sample food during the feasts. She also began to experiment. She wiped vaseline on the edges of the camera lens to create distortions in her images. Using infrared film, at the time employed in topographical studies, she lit up the forest and reinforced the dreamlike atmosphere.

The Catholic mission in the Catrimani River region served as a base of support. From there, Andujar photographed different groups, divided into huts that sheltered dozens of people. Each community had their own name (thëri) to refer to the specific details of the fauna, the flora and the place in which they were situated.

Andujar contracted malaria in 1972, which forced her to spend the following year in São Paulo. The months she spent there were productive: she studied Yanomami culture and used her apartment to test out forms of photography in low lighting. She taught classes at São Paulo Museum of Art (Masp) and organized a projection of her first Yanomami images rephotographed using color filters, a resource with which she experimented in the 1960s. In 1974, she went back on increasingly longer stays. She was determined to live in the forest.

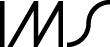

These images evoke the complex, mythical and mystical world of the Yanomami. Freed from the constraints of journalism and anthropology, Andujar gave concrete form to a symbolic repertoire inhabited by invisible entities and abstract concepts. Rays of light cross the atmosphere. A young man reclines while enveloped in smoke. Bonfires illuminate nocturnal creatures. A ceiling transforms into a starry night sky. Reflections, mirrors and dreams appear again and again, while photographic filters bathe the images in dreamlike colors.

Scenes of everyday life give origin to a photography that transcends reality, exploring the metaphysical dimension of the image. The intimacy allows Andujar to recruit the Yanomami to play an active role in the representation of their universe.

One of the most impressive sets documents the funerals and ceremonies of inter-community alliance (reahu). These parties, which can last days or even weeks, obey a sequence of specific rituals, in which they pay homage to the dead, exchange news and announcements, form romantic pairs and reestablish bonds with groups of invited neighbors. The plenitude of food is indispensable.

Andujar developed distinct forms to photograph every rite of the festivities, using elementary photographic resources, in addition to flashes, lamps and lights that she brought from the city. Multiple exposures in a single photogram allowed her to overlap and multiply elements, reinforcing the incessant repetition and the phantasmagorical atmosphere of the rituals. The dearth of light transformed rapid movements into blurs, suggesting visual spectrums. The agitation of the camera at the time of the shot transformed points of light into stains and streaks of light. The use of vaseline on the lens created a radial blur that enhanced the sensation of vertigo. Chants and speech seem visible.

Andujar produces images that have a direct connection to the mythical content, amplifying the meaning of that which is photographed rather than simply documenting it. By representing the invisible, she visually interprets a culture, with the complexity of meanings that only images are capable of accommodating.

Andujar developed this series of portraits using only the natural light that penetrated the huts. Children, adolescents, adults and the elderly emerge against a black background. Each portrait consumed an entire roll, a measure necessary for this intimacy. In addition to the physiognomical diversity, details of bodies and cultural elements appear, such as a female loincloth and waist strings.

The photographer’s position at the height of the subject portrayed, whether tall or short, old or young, reinforces the sense of complicity. Her dedication to her new friends is a way to reestablish emotional bonds and overcome the family traumas caused by the war.

The Yanomami avoid photographs, which remove individuals from their own image. When someone dies, everything that reminds others of them should destroyed, including photos. Andujar’s portraits were spared because they became instruments of dissemination and defense, protecting these people and their culture.

In 1974, with the help of the missionary Carlo Zacquini, Andujar decided to further advance the project of cultural interpretation and proposed that the Yanomami produce their drawings. Enchanted with the result, she received a grant from fapesp (São Paulo Research Foundation) in 1976 to expand the work.

She began a new chapter, offering the Yanomami paper and marker pens so that they could represent their own world. The grant money allowed her to transport kilos of material in a black vw bug, nicknamed Watupari (a vulture spirit), which she drove from São Paulo to Boa Vista. The elaborate graphic universe of the Yanomami took on new life. “After roughly five months of work, we had over 100 drawings. Sometimes, the same myth is repeated with different interpretations. The Yanomami are quite informal, with an extremely vast imagination. In general, characters from the past blend with those from the present”, she remembers.

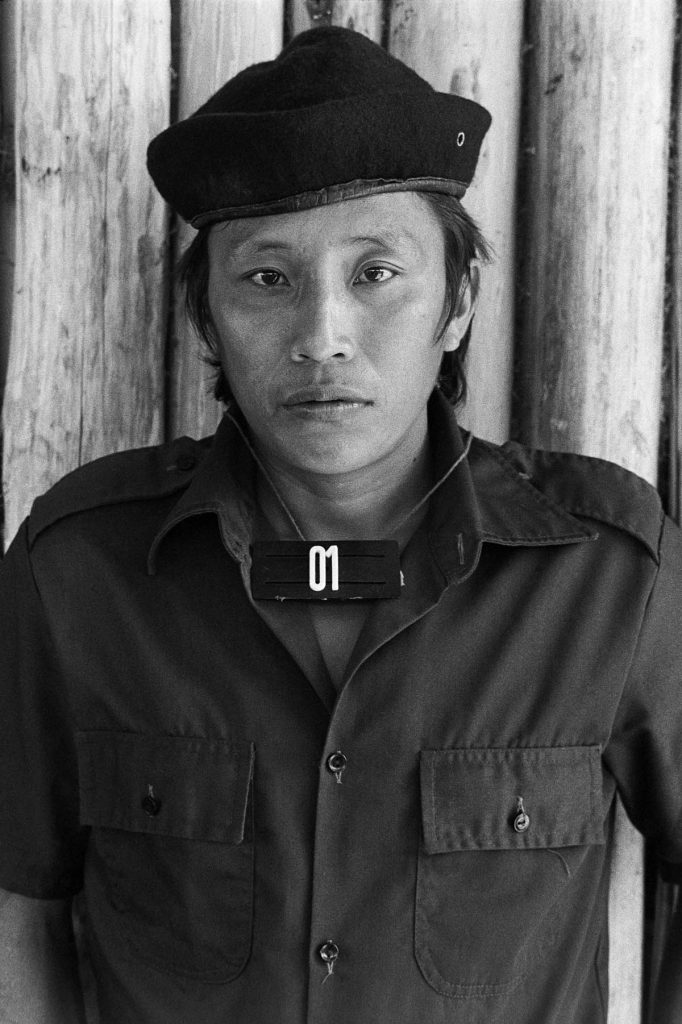

In 1980, Claudia Andujar allied with two doctors and began a healthcare project to slow the advancing diseases. This work expanded with the participation of national and international agencies. Andujar attended and photographed hundreds of Yanomami on travels throughout the entire indigenous territory, an experience that was fundamental in the execution of the ccpy’s work.

Since the Yanomami don’t possess a set name the same way that white people do, Andujar created numbered photographic portraits to identify the patients’ charts. Viewed today, the images carry multiple meanings. As individual portraits, they show us “poses” by individuals unfamiliar with photography. Organized by region, they reveal physical and cultural characteristics, and different levels of contact. As a collective register of a people, they lay bare the paradox of those marked and photographed by a society in order to be saved from the violence imposed on them by that same society.

“It’s not about justifying the mark placed on their chest, but about specifying the fact that it refers to a sensitive, ambiguous terrain that can arouse discomfort and pain,” summarizes Andujar, whose personal story adds an unavoidable parallel between these photographies and the Jews killed in Holocaust.

This installation is an audiovisual manifesto created to fight for the Yanomami people’s survival. Its original version was exhibited in São Paulo in 1989 as a reaction to the decrees signed by the president of the republic, José Sarney, who demarcated the indigenous lands in 19 isolated “islands.” The isolation of these communities would eventually lead to their asphyxiation.

Comprised of photos from Andujar’s archive rephotographed using lights and filters, the projection guides spectators through a world in harmony, gradually destroyed by the progress of white civilization. Composer Marlui Miranda created the soundtrack which combines instrumental American music, Japanese music and Yanomami chants. The ghostly appearance of the images also suggests the extermination of a people and a way of life.